Disclaimer: Sex trafficking is a complex global issue. Definitions differ and studies and statistics vary depending on the country, region, or population examined. Sex trafficking is also notoriously underreported. We operate with the information available while understanding these challenges.

Sex trafficking affects the entire world and all of the people in it. We often talk about what sex trafficking is not, such as the debunked Wayfair or Pizzagate theories or the false idea that mask-wearing to protect from COVID-19 is connected with child trafficking. None of these are accurate portrayals of sex trafficking.

So what actually is it, and how does it work?

While sex trafficking as a social issue is not a conspiracy theory, there are conspiracy theories about sex trafficking. These theories are easier to believe because of true stories that sound similar. Jeffrey Epstein was an example of a wealthy man abusing his power to traffic teenagers and young women. He is a reminder to the world that exploiters can and do come from all walks of life.

Related: 5 Myths You’ve Probably Heard About Child Sex Trafficking

Big stories like Epstein remind the public that sex trafficking is far from eradicated, but the stories and stats we hear are only the tip of the iceberg. These headlines can raise awareness, but can also perpetuate the “Hollywood narrative”—that all sex trafficking involves kidnapping, physical bondage, violence, or transportation to another country. To be clear, sex trafficking can and does happen this way, but it is a myth to believe all or most sex trafficking cases do.

Most sex trafficking scenarios do not make international headlines or trend on social media. This is because the daily realities of sex trafficking are different from the Hollywood script we imagine, yet are equally horrible and unacceptable.

The basics of trafficking explained

Sex trafficking is one version of modern-day slavery. It exists in countries all across the globe, including the United States. It occurs in cities, suburban neighborhoods, and rural communities; online, as in pay to view webcam shows, or in-person, such as prostitution and commercial sex.

The US government’s Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) 2000 defines sex trafficking as a commercial sex act “induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age.”

Related: Is Wayfair Really Sex Trafficking Children?

For example, if an adult is tricked or forced into performing in pornography, it is sex trafficking. If a “prostituted person” in a brothel is under 18 years of age, they are not considered to be a prostitute but a trafficking victim simply because of their age and their legal inability to consent.

In this definition, transportation is not included, nor is it a requirement. Human smuggling—transporting a human illegally across a border—is a different crime although the two can be related. Many sex trafficking victims are transported across national or state borders, but victims have also been trafficked from within their own homes to their own communities.

The traffickers

Traffickers used to be called “pimps,” but every year our society evolves in better understanding this issue, including accurately naming the crime. Traffickers are typically adults, male or female, who demonstrate control over a victim.

Traffickers come from all socio-economic backgrounds. Some use their wealth and power as a means of control while others experience the same financial struggles or economic oppression as their victims. Common examples include intimate partners, family members, foster parents, friends, gangs, and trusted adults posing as a benefactor.

Related: Why Do Some People Fight Against Sex Trafficking But Unconditionally Support Porn?

Force, fraud, or coercion happen in many different ways, including physical, sexual, emotional, or economic abuse. Traffickers may also use intimidation tactics, threats of harm, denial, blame, and isolation to wield control over their victim.

One of the most pervasive myths is that sex trafficking is always a violent crime. Violence can and does occur, but not all traffickers use physical force. Many look for a vulnerability within a victim that they can exploit. Traffickers often groom their victims for the purpose of sex trafficking by building a relationship and sense of trust through a process of manipulation.

Some traffickers enforce quotas or performance incentives. One study looking at sex trafficking revenues in eight US cities between 2003 and 2007 revealed 18 percent of traffickers said they impose a dollar figure quota that their “employees” were required to earn each day. Depending on the day of the week, the quotas ranged from $400 to $1,000. Some traffickers strongly enforced the quota by sending the victim back to the street to keep working until her quota was met.

From the same study, the commercial sex price set by the trafficker was most commonly calculated per hour. The cost is flexible and varies depending on the trafficker setting the price. For example, one respondent in San Diego charged $60 for 30 minutes, $120 for an hour. A respondent in Denver charged $150 for a half-hour, $250 for a full. While prices could rise to $1,000, it appears more common for sex acts to cost less than a couple hundred dollars.

Considering the price ranges and the quotas together, we can do some easy math and assume the sad reality of victims being exploited multiple times in one day.

The victims

Victims and survivors across the globe are diverse, and their experiences of how they were lured, tricked, or forced into trafficking situations also ranges. That being said, traffickers prey on vulnerable individuals or look for a vulnerability they can exploit. This could be several different things, including poverty, recent migration or relocation, substance use, mental health concerns, involvement with the child welfare system, and runaway or homeless youth.

Some victims become romantically involved with someone who later forces or manipulates them into selling sex. Others are lured with false promises of a job. Some are forced to sell sex by family members or kicked out of home by parents without any way to provide for themselves. Homeless youth are in precarious financial situations and may trade sex for food or shelter. Victims of sex trafficking may be involved in a trafficking situation for a few hours, a few days or may remain in the industry for years. The time involved doesn’t make something sex trafficking or not, only the circumstances surrounding a situation do.

Just as sex trafficking does not always involve violence, victims are not always physically restrained. This myth persists because our society correctly views sex trafficking as a horrible thing, but we then assume that victims will risk everything to escape. But there are unseen barriers that are very real to the victim. Their invisible ball and chain may be financial or they may lack basic necessities (transportation or a safe place) to leave. Some victims have been groomed to believe their trafficker is their boyfriend, benefactor, protector, or provider, and that their relationship is not controlling or exploitative.

In parts of U.S., there is evidence that people of color are disproportionately victimized by sex trafficking. While national statistics are not conclusive, there are regional examples, such as Louisianna where Black girls comprise of nearly 49 percent of child sex trafficking victims while only making up about 19 percent of the youth population. Similarly in Nebraska, 50 percent of individuals sold online for sex are Black despite Black people making up 5 percent of the population.

There are a couple of contributing reasons why this is happening. Economic inequality or attitudes and stereotypes about Black women and girls such as adultification—the idea that our society responds to Black girls as if they are fully developed adults, meaning in cases of child sex trafficking they are incorrectly believed to be “willfully engaging” instead of seen as victims—can make them more vulnerable to sex trafficking.

We often associate men and boys as victims of labor trafficking and women and girls as sex trafficking victims, but this is not the full picture. Men and boys can be victims of sex trafficking, and the belief in gender stereotypes is part of the reason why it is difficult for researchers to get accurate data on how many males are affected.

A lack of support (such as aftercare homes for males) and stigma (the idea that boys can fight back or escape from a trafficker) make it difficult for victims to report and seek help. LGBTQ boys and young men are particularly vulnerable, as they are more likely to experience homelessness. Up to 40 percent of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ and of those, 46 percent ran away from home due to family rejection.

The buyers

The men and women who purchase sex in-person or online are known as buyers. They were previously referred to as “johns” as it is men who buy sex at much higher rates than women. According to US national surveys, between 10 and 20 percent of men—or one in five or six—have admitted to purchasing sex. That being said, the commercial sex industry relies on a small percentage of men who are frequent or habitual buyers.

There is no single profile of a sex buyer. They come from all over the country, all classes, and backgrounds. That being said, a large proportion are white males. Some may fit the stereotype of being lonely dissatisfied men, but a large portion are well-educated, employed, married, and do not have an extensive criminal record.

While traffickers are largely motivated by money, buyer motivations are all over the map. When surveyed, buyers express dozens of different motivations for why they purchase sex. These can be grouped into five categories: desire for intimacy, desire for intimacy-free sex, variety, thrill seeking (drawn to illicit activities), and pathology (with intent to cause harm).

According to Michael Shively, Senior Advisor on Research and Data Analysis at the U.S. based National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE), the buyers who fall into the pathology category are the smallest percentage but they tend to commit the most abuse. One study revealed 36 percent of participating sex sellers had seen an abusive or violent client.

Buyers are not particularly sensitive or aware of the consequences of their actions. They are looking to get a need met and feel entitled to do so, but most do not intend to cause harm. Many prefer to believe the women they are buying sex from are in the industry voluntarily.

What’s the solution?

If we could magically rescue all victims from trafficking and justly punish all traffickers, everyone would take that option. But even if we could, trafficking would return because of demand. Buyers want to pay for sex, and traffickers see an opportunity to make money and coerce victims to make it happen.

To combat sex trafficking, we need a multi-faceted solution. We must rescue victims, bring justice to traffickers, and hold buyers accountable.

Related: By The Numbers: Is The Porn Industry Connected To Sex Trafficking?

Demand is also fueled by our culture. One undeniable example is the normalization of pornography. Porn consumption can breed a sense of sexual entitlement allowing consumers to feel that they are right to want the things they have seen in porn and that it’s okay to buy it. But this is not acceptable, or healthy.

It may not be easy, but the first thing you can do to fight sex trafficking is to make sure you aren’t consuming it. The sure way to do this is to refuse to click porn and porn sites, and educate others in your community on the realities of sexual exploitation.

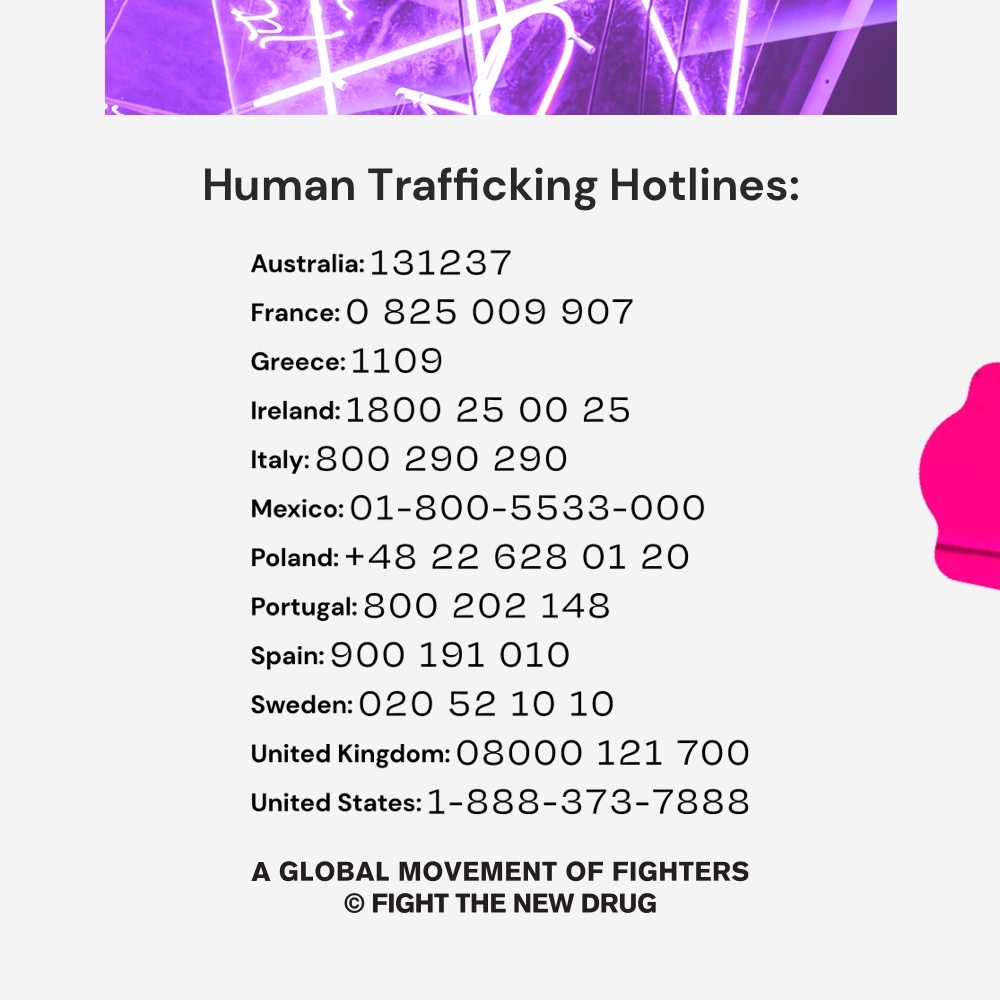

If a child is missing, the child’s legal guardian should immediately call law enforcement and then the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children at 1-800-THE-LOST® (1-800-843-5678). If you suspect a case of CHILD SEX TRAFFICKING, you can call 1-800-THE-LOST® or make a report at CyberTipline.org.

Your Support Matters Now More Than Ever

Most kids today are exposed to porn by the age of 12. By the time they’re teenagers, 75% of boys and 70% of girls have already viewed itRobb, M.B., & Mann, S. (2023). Teens and pornography. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense.Copy —often before they’ve had a single healthy conversation about it.

Even more concerning: over half of boys and nearly 40% of girls believe porn is a realistic depiction of sexMartellozzo, E., Monaghan, A., Adler, J. R., Davidson, J., Leyva, R., & Horvath, M. A. H. (2016). “I wasn’t sure it was normal to watch it”: A quantitative and qualitative examination of the impact of online pornography on the values, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of children and young people. Middlesex University, NSPCC, & Office of the Children’s Commissioner.Copy . And among teens who have seen porn, more than 79% of teens use it to learn how to have sexRobb, M.B., & Mann, S. (2023). Teens and pornography. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense.Copy . That means millions of young people are getting sex ed from violent, degrading content, which becomes their baseline understanding of intimacy. Out of the most popular porn, 33%-88% of videos contain physical aggression and nonconsensual violence-related themesFritz, N., Malic, V., Paul, B., & Zhou, Y. (2020). A descriptive analysis of the types, targets, and relative frequency of aggression in mainstream pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(8), 3041-3053. doi:10.1007/s10508-020-01773-0Copy Bridges et al., 2010, “Aggression and Sexual Behavior in Best-Selling Pornography Videos: A Content Analysis,” Violence Against Women.Copy .

From increasing rates of loneliness, depression, and self-doubt, to distorted views of sex, reduced relationship satisfaction, and riskier sexual behavior among teens, porn is impacting individuals, relationships, and society worldwideFight the New Drug. (2024, May). Get the Facts (Series of web articles). Fight the New Drug.Copy .

This is why Fight the New Drug exists—but we can’t do it without you.

Your donation directly fuels the creation of new educational resources, including our awareness-raising videos, podcasts, research-driven articles, engaging school presentations, and digital tools that reach youth where they are: online and in school. It equips individuals, parents, educators, and youth with trustworthy resources to start the conversation.

Will you join us? We’re grateful for whatever you can give—but a recurring donation makes the biggest difference. Every dollar directly supports our vital work, and every individual we reach decreases sexual exploitation. Let’s fight for real love: