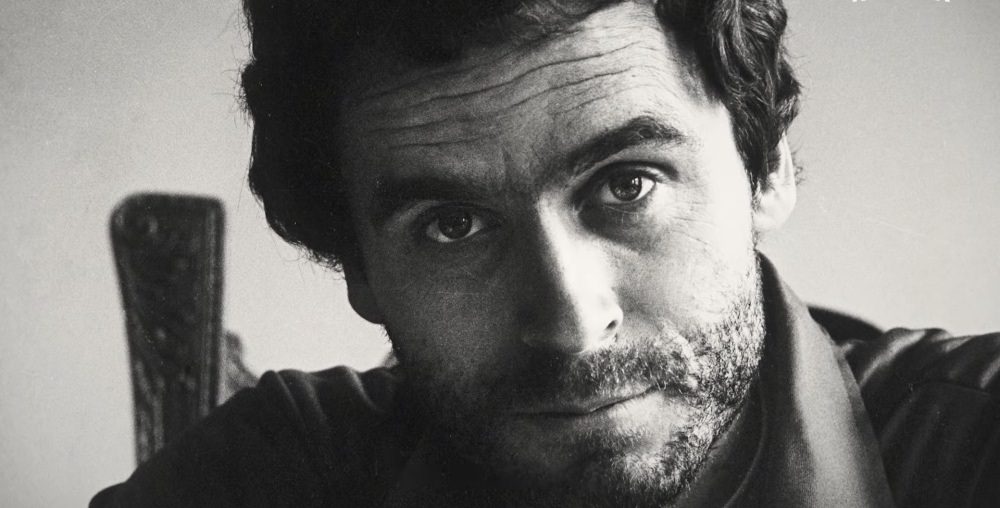

Cover photo from YouTube/Netflix. 7 minute read.

Ted Bundy. It’s a name that will send chills down your spine and give you nightmares, if you know who he is and what he’s done.

Long story short, he’s one of the most infamous mass serial killers from the 20th century. His crimes are too horrific and gruesome for us to describe here, and yet he’s become a household name. This year, on the 30th anniversary of his execution date for the rape and murder of over 30 women, Netflix dropped a brand new documentary series titled, Conversation With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes. And this week, the biopic “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile” starring Zac Efron as Bundy dropped to Netflix, too.

There’s been a lot of talk since we became an organization 10 years ago about how the crimes Ted Bundy is known for today may connect with a deep, dark porn past. Where does this shocking information come from?

In the last interview he gave before he was executed, he talked extensively about the impact porn had on him in his formative years and how he became desensitized to the objectification and abuse of women early on.

“The most damaging kinds of pornography are those that involve violence and sexual violence,” he said.

But this is a serial killer we’re hearing from who also had sociopathic tendencies, likely telling well-known anti-porn activist Dr. James Dobson what he wanted to hear, so we need to take what he said in this interview with a grain of salt—while also considering the facts.

Before we go any further, we should note that we do not believe a porn habit automatically turns people into serial killers without any other factors. We also do not believe every porn consumer will develop violent tendencies, nor will every consumer become addicted.

That being said, there are massively important facts about how violent porn—which has become mainstream—impacts our world today in measurable, real ways.

Whether Ted Bundy was telling the truth in his last interview or not, there’s a lot of research to consider.

1. Consuming violent porn normalizes sexual violence.

A few years ago, a team of researchers looked at 50 of the most popular porn films—the ones purchased and rented most often. [1] Of the 304 scenes the movies contained, 88% contained physical violence and 49% contained verbal aggression. On average, only one scene in 10 didn’t contain any aggression, and the typical scene averaged 12 physical or verbal attacks. One particularly disturbing scene managed to fit in 128!

The amount of violence shown in porn is astonishing but equally disturbing is the reaction of the victims. In the study, 95% of the victims (almost all of them women) either were neutral to the abuse or appeared to respond with pleasure. [2]

In other words, in porn, people are getting beaten up and they’re smiling about it.

Of course, not all porn features physical violence, but even non-violent porn has been shown to have effects on consumers. The vast majority of porn—violent or not—portrays men as powerful and in charge; while women are submissive and obedient. [3] Watching scene after scene of dehumanizing submission makes it start to seem normal. [4] It sets the stage for lopsided power dynamics in couple relationships and the gradual acceptance of verbal and physical aggression against women. [5] Research has confirmed that those who consume porn (even if it’s nonviolent) are more likely to support statements that promote abuse and sexual aggression toward women and girls. [6]

2. Consuming violent porn is connected with aggressive behavior.

But porn doesn’t just change attitudes; it can also shape actions. Study after study has shown that consumers of violent and nonviolent porn are more likely to use verbal coercion, drugs, and alcohol to coerce individuals into sex. [7] And multiple studies have found that exposure to both violent and nonviolent porn increases aggressive behavior, including both having violent fantasies and actually committing violent assaults. [8]

In 2016, a team of leading researchers compiled all the research they could find on the subject. [9] After examining twenty-two studies they concluded that the research left, “little doubt that, on the average, individuals who consume pornography more frequently are more likely to hold attitudes conducive [favorable] to sexual aggression and engage in actual acts of sexual aggression.”

If you’re wondering how sitting in a chair consuming porn can actually change what a person thinks and does, the answer goes back to how porn affects the brain (See How Porn Changes The Brain). Our brains have what scientists call “mirror neurons”—brain cells that fire not only when we do things ourselves, but also when we watch other people do things. [10] This is why movies can make us cry or feel angry or scared. Essentially, mirror neurons let us share the emotion of other people’s experiences as we watch. So when a person is looking at porn, he or she naturally starts to respond to the emotions of the actors seen on the screen. As the consumer becomes aroused, his or her brain gets to work wiring together those feelings of arousal to what is seen happening on the screen, almost as if he or she was actually having the experience. [11] So if a person feels aroused watching a man or woman get kicked around and called names, that individual’s brain learns to associate that kind of violence with sexual arousal. [12]

To make matters worse, when porn shows victims of violence who seem to accept or enjoy being hurt, the viewer is fed the message that people like to be treated that way, giving porn consumers a sense that it’s okay to act aggressively themselves. [13]

3. Porn convinces consumers that violence is sexy and acceptable.

Consumers might tell themselves that they aren’t personally affected by porn, that they won’t be fooled into believing its underlying messages, but studies suggest otherwise. There is clear evidence that porn makes many consumers more likely to support violence against women, to believe that women secretly enjoy being raped, [14]and to actually be sexually aggressive in real life. [15] The aggression may take many forms including verbally harassing or pressuring someone for sex, emotionally manipulating them, threatening to end the relationship unless they grant favors, deceiving them or lying to them about sex, or even physically assaulting them. [16]

And remember that porn use frequently escalates over time, so even if consumers don’t start out watching violent porn, that may change. (See Why Consuming Porn Is An Escalating Behavior.) The longer they consume, the more likely they’ll find themselves seeking out increasingly shocking, hardcore content. [17]

Not surprisingly, the more violent the porn they consume, the more likely they will be to support violence and act out violently. [18] In fact, one study found that those with higher exposure to violent porn were six times more likely to have raped someone than those who had low past exposure. [19]

What does all of this matter to the average consumer?

So, did porn make Ted Bundy into what he grew to be? There’s no real way for us to know. But if he did have a heavy porn habit, it likely didn’t sway him away from his already dangerous tendencies given what we know from decades of research by major institutions.

Not only that, we do not believe every porn consumer is going to turn into a Ted Bundy because of the availability and accessibility of violent porn—but that doesn’t make porn blameless or harmless. It can no longer be denied that pornography is hitting society with a tidal wave of dehumanizing violence, and we’re just beginning to understand the real-life impacts of it.

You don’t have to agree with the research to understand something else important: it makes no sense for our society to accept the messages of porn, while at the same time calling for full gender equality and an end of sexual assault. Many of those who will watch Netflix’s Ted Bundy documentary series will likely also log on to their favorite porn site days or hours later and consume content that fetishizes disturbing sexual abuse, and worse.

A large portion of the porn consumed by millions of people every day is reinforcing the message that humiliation and violence are normal parts of what sex is supposed to be. [20] It’s wiring the minds and expectations of the upcoming generation, making it harder for many young people to prepare for loving, nurturing relationships [21] and leaving both women and men feeling like they can’t express the pain it’s causing them. [22]

This is why we exist, as an organization, to raise awareness that porn is anything but harmless personal entertainment. Given the growing body of research, porn is, at best, a sure way to hurt your relationships, and at worst, a normalizer and fueling factor of sexual violence. Consider the facts before consuming.

Citations

[1] Bridges, A. J., Wosnitzer, R., Scharrer, E., Sun, C. & Liberman, R. (2010). Aggression And Sexual Behavior In Best Selling Pornography Videos: A Content Analysis Update. Violence Against Women, 16(10), 1065–1085. Doi:10.1177/1077801210382866

[2] Bridges, A. J., Wosnitzer, R., Scharrer, E., Sun, C. & Liberman, R. (2010). Aggression And Sexual Behavior In Best Selling Pornography Videos: A Content Analysis Update. Violence Against Women, 16(10), 1065–1085. Doi:10.1177/1077801210382866. See Also Whisnant, R. (2016). Pornography, Humiliation, And Consent. Sexualization, Media, & Society, 2(3), 1-7. Doi:10.1177/2374623816662876 (Arguing That “Pornography’s

[3] DeKeseredy, W. (2015). Critical Criminological Understandings Of Adult Pornography And Women Abuse: New Progressive Directions In Research And Theory. International Journal For Crime, Justice, And Social Democracy, 4(4) 4-21. Doi:10.5204/Ijcjsd.V4i4.184; Rothman, E. F., Kaczmarsky, C., Burke, N., Jansen, E., & Baughman, A. (2015). “Without Porn…I Wouldn’t Know Half The Things I Know Now”: A Qualitative Study Of Pornography Use Among A Sample Of Urban, Low-Income, Black And Hispanic Youth. Journal Of Sex Research, 52(7), 736-746. Doi:10.1080/00224499.2014.960908; Layden, M. A. (2010) Pornography And Violence: A New Look At The Research. In Stoner, J. & Hughes, D. (Eds.), The Social Cost Of Pornography: A Collection Of Papers (Pp. 57-68). Princeton, N.J.: Witherspoon Institute; Ryu, E. (2008). Spousal Use Of Pornography And Its Clinical Significance For Asian-American Women: Korean Woman As An Illustration. Journal Of Feminist Family Therapy, 16(4), 75. Doi:10.1300/J086v16n04_05; Shope, J. H. (2004). When Words Are Not Enough: The Search For The Effect Of Pornography On Abused Women. Violence Against Women, 10(1), 56-72. Doi:10.1177/1077801203256003

[4] Rothman, E. F., Kaczmarsky, C., Burke, N., Jansen, E., & Baughman, A. (2015). “Without Porn…I Wouldn’t Know Half The Things I Know Now”: A Qualitative Study Of Pornography Use Among A Sample Of Urban, Low-Income, Black And Hispanic Youth. Journal Of Sex Research, 52(7), 736-746. Doi:10.1080/00224499.2014.960908; Weinberg, M. S., Williams, C. J., Kleiner, S., & Irizarry, Y. (2010). Pornography, Normalization And Empowerment. Archives Of Sexual Behavior, 39 (6) 1389-1401. Doi:10.1007/S10508-009-9592-5; Doring, N. M. (2009). The Internet’s Impact On Sexuality: A Critical Review Of 15 Years Of Research. Computers In Human Behavior, 25(5), 1089-1101. Doi:10.1016/J.Chb.2009.04.003; Zillmann, D. (2000). Influence Of Unrestrained Access To Erotica On Adolescents’ And Young Adults’ Dispositions Toward Sexuality. Journal Of Adolescent Health, 27, 2: 41–44. Retrieved From Https://Www.Ncbi.Nlm.Nih.Gov/Pubmed/10904205

[5] Layden, M. A. (2010). Pornography And Violence: A New Look At The Research. In J. Stoner And D. Hughes (Eds.) The Social Costs Of Pornography: A Collection Of Papers (Pp. 57–68). Princeton, NJ: Witherspoon Institute; Berkel, L. A., Vandiver, B. J., & Bahner, A. D. (2004). Gender Role Attitudes, Religion, And Spirituality As Predictors Of Domestic Violence Attitudes In White College Students. Journal Of College Student Development, 45:119–131. Doi:10.1353/Csd.2004.0019; Allen, M., Emmers, T., Gebhardt, L., And Giery, M. A. (1995). Exposure To Pornography And Acceptance Of The Rape Myth. Journal Of Communication, 45(1), 5–26. Doi:10.1111/J.1460-2466.1995.Tb00711.X

[6] Hald, G. M., Malamuth, N. M., And Yuen, C. (2010). Pornography And Attitudes Supporting Violence Against Women: Revisiting The Relationship In Nonexperimental Studies. Aggression And Behavior, 36(1), 14–20. Doi:10.1002/Ab.20328; Berkel, L. A., Vandiver, B. J., And Bahner, A. D. (2004). Gender Role Attitudes, Religion, And Spirituality As Predictors Of Domestic Violence Attitudes In White College Students. Journal Of College Student Development, 45(2), 119–131. Doi:10.1353/Csd.2004.0019; Zillmann, D. (2004). Pornografie. In R. Mangold, P. Vorderer, & G. Bente (Eds.) Lehrbuch Der Medienpsychologie (Pp. 565–85). Gottingen, Germany: Hogrefe Verlag; Zillmann, D. (1989). Effects Of Prolonged Consumption Of Pornography. In D. Zillmann & J. Bryant, (Eds.) Pornography: Research Advances And Policy Considerations (P. 155). Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

[7] Boeringer, S. B. (1994). Pornography And Sexual Aggression: Associations Of Violent And Nonviolent Depictions With Rape And Rape Proclivity. Deviant Behavior 15(3), 289–304; Doi:10.1080/01639625.1994.9967974; Check, J. & Guloien, T. (1989). The Effects Of Repeated Exposure To Sexually Violent Pornography, Nonviolent Dehumanizing Pornography, And Erotica. In D. Zillmann & J. Bryant (Eds.) Pornography: Research Advances And Policy Considerations (Pp. 159–84). Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Marshall, W. L. (1988). The Use Of Sexually Explicit Stimuli By Rapists, Child Molesters, And Non-Offenders. Journal Of Sex Research, 25(2): 267–88. Doi:10.1080/00224498809551459

[8] Wright, P.J., Tokunaga, R. S., & Kraus, A. (2016). A Meta-Analysis Of Pornography Consumption And Actual Acts Of Sexual Aggression In General Population Studies. Journal Of Communication, 66(1), 183-205. Doi:10.1111/Jcom.12201; DeKeseredy, W. (2015). Critical Criminological Understandings Of Adult Pornography And Women Abuse: New Progressive Directions In Research And Theory. International Journal For Crime, Justice, And Social Democracy, 4(4) 4-21. Doi:10.5204/Ijcjsd.V4i4.184; Allen, M., Emmers, T., Gebhardt, L., & Giery, M. A. (1995). Exposure To Pornography And Acceptance Of The Rape Myth. Journal Of Communication, 45(1), 5–26. Doi:10.1111/J.1460-2466.1995.Tb00711.X

[9] Wright, P.J., Tokunaga, R. S., & Kraus, A. (2016). A Meta-Analysis Of Pornography Consumption And Actual Acts Of Sexual Aggression In General Population Studies. Journal Of Communication, 66(1), 183-205. Doi:10.1111/Jcom.12201

[10] Rizzolatti, G. And Craighero, L. (2004). The Mirror-Neuron System. Annual Review Of Neuroscience 27, 169–192. Doi:10.1146/Annurev.Neuro.27.070203.144230

[11] Hilton, D. L. (2013). Pornography Addiction—A Supranormal Stimulus Considered In The Context Of Neuroplasticity. Socioaffective Neuroscience & Psychology 3:20767. Doi:10.3402/Snp.V3i0.20767; Doidge, N. (2007). The Brain That Changes Itself. New York: Penguin Books.

[12] Layden, M. A. (2010). Pornography And Violence: A New Look At The Research. In J. Stoner And D. Hughes (Eds.) The Social Costs Of Pornography: A Collection Of Papers (Pp. 57–68). Princeton, NJ: Witherspoon Institute; Doidge, N. (2007). The Brain That Changes Itself. New York: Penguin Books; Malamuth, N. M. (1981). Rape Fantasies As A Function Of Exposure To Violent Sexual Stimuli. Archives Of Sexual Behavior 10(1), 33–47. Doi:10.1007/BF01542673

[13] Bridges, A. J. (2010). Pornography’s Effect On Interpersonal Relationships. In J. Stoner And D. Hughes (Eds.) The Social Costs Of Pornography: A Collection Of Papers (Pp. 89-110). Princeton, NJ: Witherspoon Institute; Layden, M. A. (2010). Pornography And Violence: A New Look At The Research. In J. Stoner And D. Hughes (Eds.) The Social Costs Of Pornography: A Collection Of Papers (Pp. 57–68). Princeton, NJ: Witherspoon Institute; Marshall, W. L. (2000). Revisiting The Use Of Pornography By Sexual Offenders: Implications For Theory And Practice. Journal Of Sexual Aggression 6(1-2), 67. Doi:10.1080/13552600008413310

[14] Layden, M. A. (2010). Pornography And Violence: A New Look At The Research. In J. Stoner And D. Hughes (Eds.) The Social Costs Of Pornography: A Collection Of Papers (Pp. 57–68). Princeton, NJ: Witherspoon Institute; Milburn, M., Mather, R., & Conrad, S. (2000). The Effects Of Viewing R-Rated Movie Scenes That Objectify Women On Perceptions Of Date Rape. Sex Roles, 43(9-10), 645–664. 10.1023/A:1007152507914; Weisz, M. G. & Earls, C. (1995). The Effects Of Exposure To Filmed Sexual Violence On Attitudes Toward Rape. Journal Of Interpersonal Violence, 10(1), 71–84; Doi:10.1177/088626095010001005; Ohbuchi, K. I., Et Al. (1994). Effects Of Violent Pornography Upon Viewers’ Rape Myth Beliefs: A Study Of Japanese Males. Psychology, Crime, And Law 7(1), 71–81; Doi:10.1080/10683169408411937; Corne, S., Et Al. (1992). Women’s Attitudes And Fantasies About Rape As A Function Of Early Exposure To Pornography. Journal Of Interpersonal Violence 7(4), 454–61. Doi:10.1177/088626092007004002; Check, J. & Guloien, T. (1989). The Effects Of Repeated Exposure To Sexually Violent Pornography, Nonviolent Dehumanizing Pornography, And Erotica. In D. Zillmann & J. Bryant (Eds.) Pornography: Research Advances And Policy Considerations (Pp. 159–84). Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Check, J. & Malamuth, N. M. (1985). An Empirical Assessment Of Some Feminist Hypotheses About Rape. International Journal Of Women’s Studies 8, 4: 414–23.

[15] Hald, G. M., Malamuth, N. M., & Yuen, C. (2010). Pornography And Attitudes Supporting Violence Against Women: Revisiting The Relationship In Nonexperimental Studies. Aggression And Behavior 36(1), 14–20. Doi:10.1002/Ab.20328; Layden, M. A. (2010). Pornography And Violence: A New Look At The Research. In J. Stoner & D. Hughes (Eds.) The Social Costs Of Pornography: A Collection Of Papers (Pp. 57–68). Princeton, NJ: Witherspoon Institute; Boeringer, S. B. (1994). Pornography And Sexual Aggression: Associations Of Violent And Nonviolent Depictions With Rape And Rape Proclivity. Deviant Behavior 15(3), 289–304. Doi:10.1080/01639625.1994.9967974; Check, J. & Guloien, T. (1989). The Effects Of Repeated Exposure To Sexually Violent Pornography, Nonviolent Dehumanizing Pornography, And Erotica. In D. Zillmann & J. Bryant (Eds.) Pornography: Research Advances And Policy Considerations (Pp. 159–84). Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Marshall, W. L. (1988). The Use Of Sexually Explicit Stimuli By Rapists, Child Molesters, And Non-Offenders. Journal Of Sex Research, 25(2): 267–88. Doi:10.1080/00224498809551459

[16] Wright, P.J., Tokunaga, R. S., & Kraus, A. (2016). A Meta-Analysis Of Pornography Consumption And Actual Acts Of Sexual Aggression In General Population Studies. Journal Of Communication, 66(1), 183-205. Doi:10.1111/Jcom.12201; DeKeseredy, W. (2015). Critical Criminological Understandings Of Adult Pornography And Women Abuse: New Progressive Directions In Research And Theory. International Journal For Crime, Justice, And Social Democracy, 4(4) 4-21. Doi:10.5204/Ijcjsd.V4i4.184; Barak, A., Fisher, W. A., Belfry, S., & Lashambe, D. R. (1999). Sex, Guys, And Cyberspace: Effects Of Internet Pornography And Individual Differences On Men’s Attitudes Toward Women. Journal Of Psychology And Human Sexuality, 11(1),63–91. Doi:10.1300/J056v11n01_04

[17] Park, B. Y., Et Al. (2016). Is Internet Pornography Causing Sexual Dysfunctions? A Review With Clinical Reports. Behavioral Sciences, 6, 17. Doi:10.3390/Bs6030017; Kalman, T.P. (2008). Clinical Encounters With Internet Pornography. Journal Of The American Academy Of Psychoanalysis And Dynamic Psychiatry, 36(4) 593-618. Doi:10.1521/Jaap.2008.36.4.593; Doidge, N. (2007). The Brain That Changes Itself. New York: Penguin Books.

[18] Hald, G. M., Malamuth, N. M., And Yuen, C. (2010). Pornography And Attitudes Supporting Violence Against Women: Revisiting The Relationship In Nonexperimental Studies. Aggression And Behavior 36(1), 14–20. Doi:10.1002/Ab.20328.; Allen, M., Emmers, T., Gebhardt, L., & Giery, M. A. (1995). Exposure To Pornography And Acceptance Of The Rape Myth. Journal Of Communication, 45(1), 5–26. Doi:10.1111/J.1460-2466.1995.Tb00711.X

[19] Boeringer, S. B. (1994). Pornography And Sexual Aggression: Associations Of Violent And Nonviolent Depictions With Rape And Rape Proclivity. Deviant Behavior 15(3), 289–304. Doi:10.1080/01639625.1994.9967974

[20] Bridges, A. J. (2010). Pornography’s Effect On Interpersonal Relationships. In J. Stoner & D. Hughes (Eds.) The Social Costs Of Pornography: A Collection Of Papers (Pp. 89-110). Princeton, NJ: Witherspoon Institute; Doidge, N. (2007). The Brain That Changes Itself. New York: Penguin Books; Layden, M. A. (2004). Committee On Commerce, Science, And Transportation, Subcommittee On Science And Space, U.S. Senate, Hearing On The Brain Science Behind Pornography Addiction, November 18.

[21] Yoder, V. C., Virden, T. B., & Amin, K. (2005). Internet Pornography And Loneliness: An Association? Sexual Addiction And Compulsivity, 12, 19-44. Doi:10.1080/10720160590933653; Brooks, G. R., (1995). The Centerfold Syndrome: How Men Can Overcome Objectification And Achieve Intimacy With Women. San Francisco, CA: Bass.

[22] Layden, M. A. (2010). Pornography And Violence: A New Look At The Research. In J. Stoner & D. Hughes (Eds.) The Social Costs Of Pornography: A Collection Of Papers (Pp. 57–68). Princeton, NJ: Witherspoon Institute; Wolf, N. (2004). The Porn Myth. New York Magazine, May 24.

Your Support Matters Now More Than Ever

Most kids today are exposed to porn by the age of 12. By the time they’re teenagers, 75% of boys and 70% of girls have already viewed itRobb, M.B., & Mann, S. (2023). Teens and pornography. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense.Copy —often before they’ve had a single healthy conversation about it.

Even more concerning: over half of boys and nearly 40% of girls believe porn is a realistic depiction of sexMartellozzo, E., Monaghan, A., Adler, J. R., Davidson, J., Leyva, R., & Horvath, M. A. H. (2016). “I wasn’t sure it was normal to watch it”: A quantitative and qualitative examination of the impact of online pornography on the values, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of children and young people. Middlesex University, NSPCC, & Office of the Children’s Commissioner.Copy . And among teens who have seen porn, more than 79% of teens use it to learn how to have sexRobb, M.B., & Mann, S. (2023). Teens and pornography. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense.Copy . That means millions of young people are getting sex ed from violent, degrading content, which becomes their baseline understanding of intimacy. Out of the most popular porn, 33%-88% of videos contain physical aggression and nonconsensual violence-related themesFritz, N., Malic, V., Paul, B., & Zhou, Y. (2020). A descriptive analysis of the types, targets, and relative frequency of aggression in mainstream pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(8), 3041-3053. doi:10.1007/s10508-020-01773-0Copy Bridges et al., 2010, “Aggression and Sexual Behavior in Best-Selling Pornography Videos: A Content Analysis,” Violence Against Women.Copy .

From increasing rates of loneliness, depression, and self-doubt, to distorted views of sex, reduced relationship satisfaction, and riskier sexual behavior among teens, porn is impacting individuals, relationships, and society worldwideFight the New Drug. (2024, May). Get the Facts (Series of web articles). Fight the New Drug.Copy .

This is why Fight the New Drug exists—but we can’t do it without you.

Your donation directly fuels the creation of new educational resources, including our awareness-raising videos, podcasts, research-driven articles, engaging school presentations, and digital tools that reach youth where they are: online and in school. It equips individuals, parents, educators, and youth with trustworthy resources to start the conversation.

Will you join us? We’re grateful for whatever you can give—but a recurring donation makes the biggest difference. Every dollar directly supports our vital work, and every individual we reach decreases sexual exploitation. Let’s fight for real love: