Disclaimer: Fight the New Drug is a non-religious and non-legislative awareness and education organization. Some of the issues discussed in the following article are legislatively-affiliated. Though our organization is non-legislative, we fully support the regulation of already illegal forms of pornography and sexual exploitation, including the fight against sex trafficking, and safeguards to protect children.

Do you know the minimum age of sexual consent in the U.S.? In most states, it’s 16, though in others it can be 17 or 18.

In other countries, though, it is much lower. In some parts of Latin America or the Asia Pacific, the minimum age is as young as 12.

Until recently in the Philippines, this was the case. In March of 2022, Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte announced that the minimum age of sexual consent would increase from 12 to 16 years.

What does the legal change entail?

The new law, the first change in almost 100 years, is gender-neutral, applying the same protection to boys and girls.

It states that it is considered statutory rape for any adult to engage in sexual activity with someone under the age of 16. The maximum sentence is 40 years in prison.

There is an exception: in the case that neither individual is under 13 years of age, the age difference between them is three years or less, and sex was “proven to be consensual, not abusive nor exploitative”—the law does not apply.

What triggered the legal change?

Many child rights’ advocacy groups have praised the legal change. UNICEF has stated that it is, “an essential step towards fulfilling children’s rights to protection from sexual violence, abuse and exploitation.”

The strong international reaction has to do with the country’s complicated past: the Philippines has historically dealt with high rates of child rape and sexual violence, and prior to this legal change had one of the world’s lowest minimum sexual consent age laws.

For decades, child activist organizations have been pushing to raise the legal age, arguing that children of 12 could, in fact, be victims of abuse, and be easily coerced or manipulated into keeping silent. This is heightened by the fact that in the Philippines, seven in ten children who are victims of violence are not aware of help services.

Now, it appears lawmakers have taken the step of changing the law to protect minors from rape and sexual assault.

Child abuse stats in the Philippines

This law appears to follow a trend toward change in the country. In 2021, President Duterte declared it a “national priority” to prevent teen pregnancies and, at the turn of 2022, banned child marriages.

This is significant in a country where one in six girls is wed before 18. In fact, historically the Philippines reports some bleak statistics when it comes to child exploitation.

In 2015, one government study found that one in five children aged 13-17 experienced sexual violence, and one in 25 had been raped during childhood. The same year, UNICEF reported that “there is a high prevalence of physical, psychological, sexual and online violence committed on Filipino children.”

That “high prevalence” translates to this: 80% of Filipino children have experienced some form of violence at home, in school, in their community, and online.

An online industry of abuse

This last location is particularly relevant as the Philippines has more recently become a hot spot for online child abuse.

According to the United Nations (UN) there are tens of thousands of children involved in an over $1 billion local child abuse industry, which at times financially sustains entire communities.

Live-streaming sites have primarily sustained this illicit online industry, facilitated by encryption capabilities that make perpetrators difficult to track. The use of English, access to the internet, international cash transfer systems, deep poverty, and vast access to vulnerable minors has enabled it to become a rapidly growing and lucrative business for abusers.

Tragically, it is often parents who agree to have their children victimized for money.

John Richmond, a State Department official overseeing U.S. efforts to address human trafficking stated that “the traffickers are actually parents or close family members of the kids they are exploiting,” a reality COVID has reportedly exacerbated as “lockdown orders mean that children are being locked down with their traffickers.”

One indication of the growth of child exploitation is seen in the increase of online reports of child sexual exploitation, or “cybertips,” that have been submitted. In just a couple of years—from 2014 to 2017—there has been a 250% increase in reports, a total number of 81,723 cybertips.

Similarly, The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) transferred close to 15,000 tips to the Philippine Office of Cybercrime, of which 80% referenced online child exploitation.

A new step forward

Undoubtedly, one child abused is one too many no matter if they’re in the Philippines or any other country.

Efforts by international organizations and child activist groups, as well as changes in legislation like this new minimum age consent law, speak to a more hopeful future ahead where child abuse will not be tolerated.

To report an incident involving the possession, distribution, receipt, or production of child pornography, file a report on the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC)’s website at www.cybertipline.com, or call 1-800-843-5678.

Your Support Matters Now More Than Ever

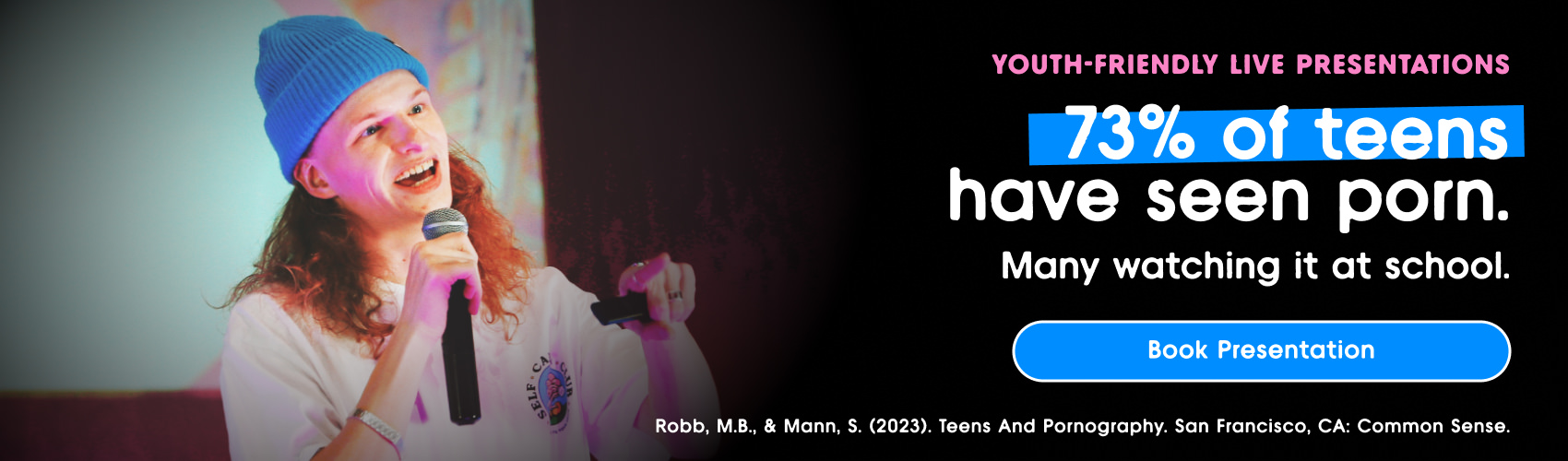

Most kids today are exposed to porn by the age of 12. By the time they’re teenagers, 75% of boys and 70% of girls have already viewed itRobb, M.B., & Mann, S. (2023). Teens and pornography. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense.Copy —often before they’ve had a single healthy conversation about it.

Even more concerning: over half of boys and nearly 40% of girls believe porn is a realistic depiction of sexMartellozzo, E., Monaghan, A., Adler, J. R., Davidson, J., Leyva, R., & Horvath, M. A. H. (2016). “I wasn’t sure it was normal to watch it”: A quantitative and qualitative examination of the impact of online pornography on the values, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of children and young people. Middlesex University, NSPCC, & Office of the Children’s Commissioner.Copy . And among teens who have seen porn, more than 79% of teens use it to learn how to have sexRobb, M.B., & Mann, S. (2023). Teens and pornography. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense.Copy . That means millions of young people are getting sex ed from violent, degrading content, which becomes their baseline understanding of intimacy. Out of the most popular porn, 33%-88% of videos contain physical aggression and nonconsensual violence-related themesFritz, N., Malic, V., Paul, B., & Zhou, Y. (2020). A descriptive analysis of the types, targets, and relative frequency of aggression in mainstream pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(8), 3041-3053. doi:10.1007/s10508-020-01773-0Copy Bridges et al., 2010, “Aggression and Sexual Behavior in Best-Selling Pornography Videos: A Content Analysis,” Violence Against Women.Copy .

From increasing rates of loneliness, depression, and self-doubt, to distorted views of sex, reduced relationship satisfaction, and riskier sexual behavior among teens, porn is impacting individuals, relationships, and society worldwideFight the New Drug. (2024, May). Get the Facts (Series of web articles). Fight the New Drug.Copy .

This is why Fight the New Drug exists—but we can’t do it without you.

Your donation directly fuels the creation of new educational resources, including our awareness-raising videos, podcasts, research-driven articles, engaging school presentations, and digital tools that reach youth where they are: online and in school. It equips individuals, parents, educators, and youth with trustworthy resources to start the conversation.

Will you join us? We’re grateful for whatever you can give—but a recurring donation makes the biggest difference. Every dollar directly supports our vital work, and every individual we reach decreases sexual exploitation. Let’s fight for real love: