Disclaimer: Fight the New Drug is a non-religious and non-legislative awareness and education organization. Some of the issues discussed in the following article are legislatively-affiliated. Including links and discussions about these legislative matters does not constitute an endorsement by Fight the New Drug. Though our organization is non-legislative, we fully support the regulation of already illegal forms of pornography and sexual exploitation, including the fight against sex trafficking.

When many people hear “human trafficking,” they picture women and children being forcibly taken and sold into sex slavery by total strangers, or locked in a dark room far from home in a foreign country.

However, this common perception is not the reality of most sex trafficking cases. Human trafficking is a complex issue, and most victims aren’t kidnapped by strangers or secret groups.

Typically it’s neighbors, relatives, romantic partners, or other acquaintances who exploit victims. Traffickers use fraud, psychological manipulation, or coercive recruitment so they often don’t need to kidnap or even physically restrain their victims.

In many cases, the psychological manipulation utilized by traffickers is much more binding than physical restraints would be.

So why the disconnect between what the mass public perceives as how sex trafficking happens, and the reality of what victims endure?

Misconceptions, misinformation, conspiracy theories, and rumors about sex trafficking have spread like wildfire throughout communities and on social media—particularly in the United States. These viral, false narratives often end up in the hands of well-intentioned people, who ultimately can hinder rather than help the work of anti-trafficking stakeholders.

Related: What Would It Take To Stop Human Sex Trafficking Forever?

For example, law enforcement becomes inundated with false information that they’re required to follow up on—stretching their already limited time and resources that could be spent on actual trafficking cases. Waves of calls and tips related to misinformation overwhelm the systems put in place to respond to potential and confirmed human trafficking cases. Rumors also mean anti-trafficking organizations and experts have to allocate time and resources to re-educate the public.

To put it simply, having accurate facts not only matters, but is crucial for fighting this issue.

Resources like the annual Trafficking in Persons Report (TIP) and the Federal Human Trafficking Report are invaluable for anyone who wants to be more educated on the realities of human trafficking.

Let’s take a look at what this year’s report reveals, and the extensive impact of COVID-19 as it relates to human trafficking and exploitation.

What is sex trafficking, really?

The Trafficking Victims Protection Act, or TVPA, was enacted on October 28, 2000. This law represented a significant milestone in the fight to end human trafficking and exploitation in all its forms—including increased efforts to hold perpetrators accountable and protect survivors.

There are many different types of human trafficking, but the TVPA defines sex trafficking, specifically, as a “commercial sex act induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such an act has not attained 18 years of age.” A victim need not be physically transported from one location to another for sex trafficking to occur—they can be sex trafficked and still collect a paycheck and sleep in their own bed at the end of the day.

There’s a framework of three elements of sex trafficking to further clarify this definition:

Acts: When a trafficker recruits, harbors, transports, provides, obtains, patronizes, or solicits another person to engages in commercial sex.

Means: When a trafficker uses force, fraud, or coercion. Coercion can include a broad array of nonviolent means, like psychosocial harm, reputational harm, threats to others, and debt manipulation.

Purpose: The purpose in every sex trafficking case is the same—to engage in a commercial sex act. Sex trafficking can take place in private homes, massage parlors, hotels, or brothels, among other locations, as well as on the internet.

Human trafficking can take place even if the victim initially consented. For example, an adult victim’s initial willingness to engage in commercial sex acts is not relevent where the perpatator subsequently uses coercion to exploit the victim and causes them to continue engaging in the same acts.

And in the case of child sex trafficking, if any individual engages in any of the above acts with a child (under the age of 18), the element of means or consent is irrelevant. A child cannot legally consent to commercial sex, and the use of children in commercial sex is prohibited by law in the United States and most countries around the world.

Related: How OnlyFans Reportedly Facilitates And Profits From Child Sex Trafficking

In other words, there’s no such thing as a “child prostitute,” there are only child trafficking victims.

The impact of COVID-19 on global sex trafficking

This year’s TIP report sends a strong message—global crises like the COVID-19 pandemic compound existing vulnerabilities to exploitation and create an ideal environment for human trafficking to evolve and flourish.

At the same time the number of individuals at risk greatly increased, resources were diverted from victims and survivors to pandemic response—and traffickers capitalized on the compounded crises.

Some of the main trafficking factors brought on by the global pandemic included:

A growing number of people experiencing economic and social vulnerabilities.

- The pandemic made significantly more people vulnerable to trafficking—including women and children, people affected by travel restrictions and stay-at-home orders, trafficking survivors, and persons impacted by economic disruption and lack of livelihood options.

- Survivors of trafficking faced increased risk of potential re-victimization due to financial and emotional hardships during the crisis.

- A survey by the Office of Security and Co-operation in Europe’s OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) and UN Women highlights revealed almost 70% of trafficking survivors from 35 countries reported that their financial well-being was heavily impacted by COVID-19, and more than two-thirds attributed a decline in their mental health to government-imposed lockdowns triggering memories of exploitive situations.

- Some survivors were pressured by former traffickers after the loss of employment options.

- Some survivors had to sell their cell phones to purchase food, further isolating them from potential assistance from caseworkers.

- Stay-at-home orders and travel limitations increased rates of gender-based violence and substance abuse, both of which put individuals at a higher risk of exploitation.

- Substantial financial difficulties coupled with the rise in costs of living and disruptions to social safety networks made people vulnerable who previously hadn’t been and increased risk for those already vulnerable to exploitation.

Related: INTERPOL Report Reveals The Disturbing Truth About COVID-19’S Impact On Child Exploitation

Traffickers quickly adapt and exploit COVID-19 related risks.

- Traffickers adapted their existing tactics to take advantage of the unique circumstances of the pandemic.

- Identifying victims became more difficult with individuals confined to their homes or workplaces and not making contact with intervention personnel like teachers, doctors, etc. (Note that mask-wearing was not a factor in identification difficulties.)

- Traffickers targeted individuals and families experiencing financial difficulties—offering fraudulent promises or job offers to recruit children, while other families exploited or sold their own children to traffickers to financially support themselves.

- Traffickers sought to re-exploit survivors who became financially unstable and vulnerable to revictimization.

- In India and Nepal, young girls from poor and rural areas were often expected to leave school to support their families during the economic hardship—with some being forced into marriage in exchange for money.

- Reports from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Uruguay show that landlords forced or coerced their tenants (often women) to have sex with them when the tenant couldn’t pay rent.

- In Haiti, Niger, and Mali, gangs operating in IDP camps took advantage of reduced security and limited protection to force residents at the camp to perform commercial sex acts.

- Traffickers capitalized on the reduced capacity and shifting priorities of law enforcement and the diversion of resources from anti-trafficking efforts, and the resulting anonymity and impunity that lowered their odds of arrest.

An increase in forms of online sexual exploitation.

- As U.S. Congressman Chris Smith shared, “Today, due to COVID-19 restrictions, young people are spending more time online, and evidence suggests a huge spike in predators’ access to children on the internet and the rise of online grooming and sexual exploitation while children are isolated and ‘virtually’ connected to the world.”

- As children spent more time online for virtual learning due to school closures, often with little parental supervision, online recruitment and grooming increased.

- Several countries reported a drastic increase in online commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking, including online sexual exploitation of children (OSEC), and demand for and distribution of child sexual exploitation material (CSEM).

- The Philippine Department of Justice noted an increase of nearly 300% in referrals for potential online sex trafficking and OSEC cases during lockdown from March to May 2020.

- India reported a 95% rise in online searches for CSEM, and India ranked among the highest countries in the world for material related to child sexual abuse found online—11.6% of global compilation of reports in 2020.

- The U.S. National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) reported a 98.66% increase in online enticement reports between January and September 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. Reports to their CyberTipline also doubled to 1.6 million.

Competing priorities and reduced capacity.

- Governments faced the predicament of shifting priorities to focus on public health and economic concerns, which drew attention and resources away from anti-trafficking efforts—including awareness campaigns in public areas, community outreach, and law enforcement investigations.

- Stay-at-home orders and travel restrictions made it more difficult for front-line officials to protect individuals through proper identification and screening techniques.

Decreased financial and human resources.

- NGO’s from various countries reported significant funding cuts due to COVID-19, forcing some to halt or cancel victim-support services.

Challenges facing victims and survivors.

- Victims and survivors faced obstacles accessing assistance and support.

- Emergency response and support services like shelters, hospitals, and clinics were overburdened, at reduced capacity, or closed.

- Self-reporting became riskier, especially for victims quarantined with their trafficker.

- Closed borders significantly decreased repatriation for trafficking survivors.

- The OSCE/UN Women survey noted that access to employment decreased by 85%, medical services by 73%, social services by 70%, legal assistance and access to food and water by 66%, psychological assistance by 64%, and access to safe accommodation by 63%.

- Many COVID-19 mitigation measures, such as mask-wearing, virtual (internet) engagements, and self-isolation, re-traumatized and exacerbated the trauma response for some survivors.

Prosecution challenges

- While law enforcement officials worked to manage COVID-19 outbreaks and were unable to conduct proper investigations and interviews, criminal justice systems often delayed and suspended prosecution efforts and experienced a backlog of cases.

- Victims who conducted interviews virtually reported feeling uncomfortable sharing their experiences with investigators before developing a relationship.

- No internet connectivity and related financial barriers made it challenging for rural or underserved areas to participate in virtual courts.

Related: We Need To Talk About Our Culture’s Sexual Obsession With Barely-18-Year-Olds

Who is particularly vulnerable to sex trafficking?

The pandemic had disproportionate effects on marginalized communities already more vulnerable to sex trafficking, like persons with disabilities, LGBTQ+ persons, indigenous peoples, and members of racial, ethnic, and religious minority groups.

Rebecca Ayling, Project Director for the New Hampshire Human Trafficking Collaborative Task Force, shared, “When people are struggling with their finances, struggling with poverty, loss of work, childhood trauma and abuse, homeless or a young person who’s not safe at home and ends up on the streets or couch surfing, all those things can lead to you being exploited by a trafficker—and those people are in every town.”

The pandemic also shed light on the complexities in familial trafficking—or when a family member or guardian is the victim’s trafficker or the one who sells the child to a third-party trafficker. In 2017, IOM estimated that 41% of child trafficking experiences are facilitated by family members and/or caregivers. One study in the TIP estimates that the trafficker is a family member in about 31% of child sex trafficking cases.

Familial trafficking is often overlooked, and is particularly difficult given the perpetrator’s close proximity to the child and their grooming the victim from a very early age. The child’s inherent loyalty to and reliance on their family members make familial trafficking difficult to identify and challenging to prosecute. The exploitation is often normalized and accepted within the family culture—sometimes spanning generations.

Related: Did You Know Men And Boys Can Be Victims Of Sex Trafficking, Too?

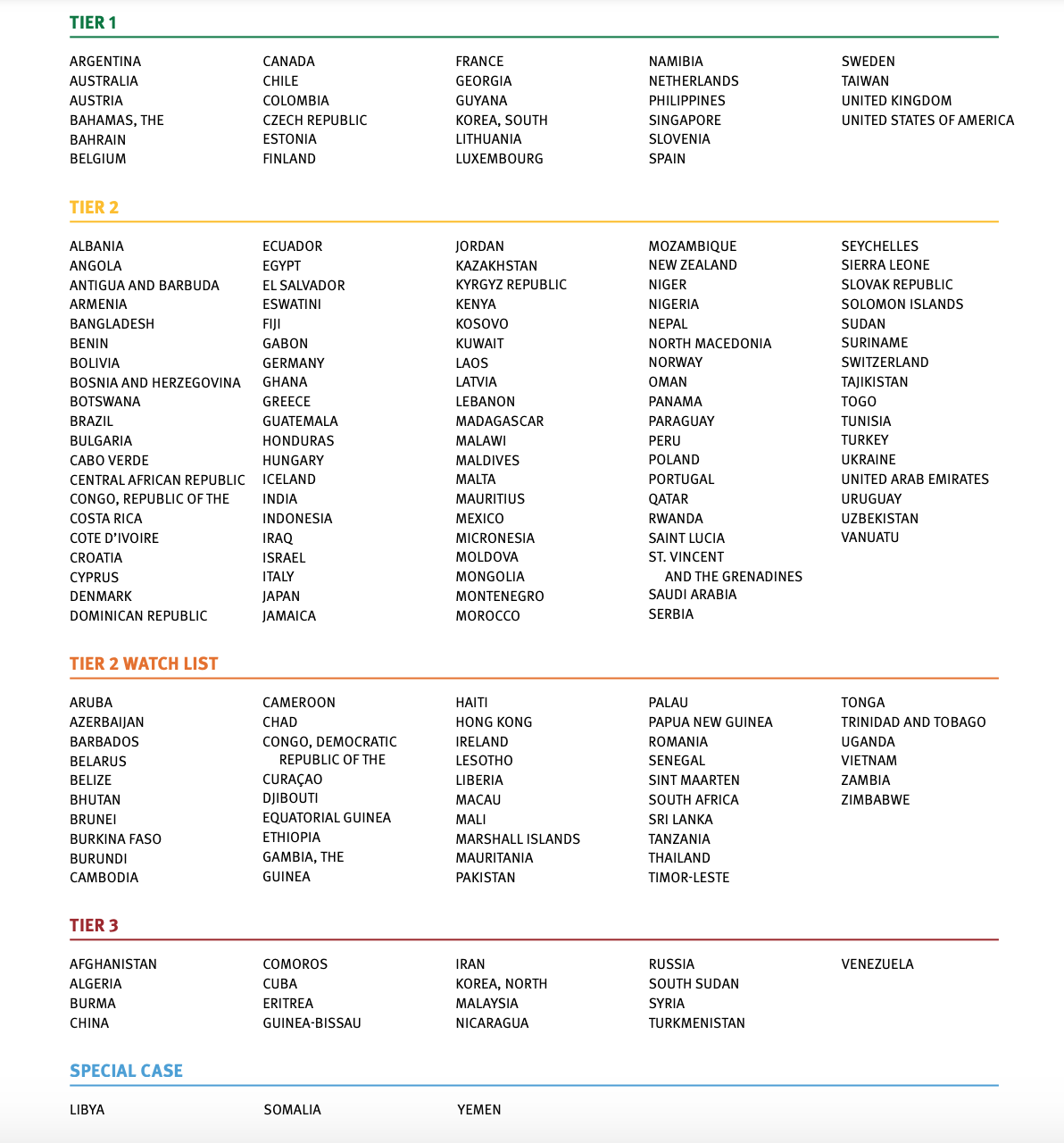

Tier Placement

The TIP report also classifies countries into one of four tiers, as mandated by the TVPA. The following are based on the extent of effort that governments have made to address the issue of human trafficking and meet the TVPA’s minimum standards—not the size of a country’s trafficking problem.

Tier 1 – Countries whose governments meet the TVPA’s minimum standards. This doesn’t mean a country has no human trafficking problems or that its doing enough to address it. Tier 1 represents a responsibility rather than a reprieve.

Tier 2 – Countries whose governments do not fully meet the TVPA’s minimum standards but are making significant efforts to bring themselves into compliance.

Tier 2 Watch List – In addition to the Tier 2 classification, these are countries for which the estimated number of victims of severe forms of trafficking is very significant or is significantly increasing and the country is not taking proportional concrete actions; or there is failure to provide evidence of increasing efforts to combat severe forms of trafficking in persons from the previous year.

Tier 3 – Countries whose governments do not fully meet the TVPA’s minimum standards and are not making significant efforts to do so. Pursuant to the TVPA, governments of countries on Tier 3 may be subject to certain restrictions on foreign assistance that are non-humanitarian and non trade-related.

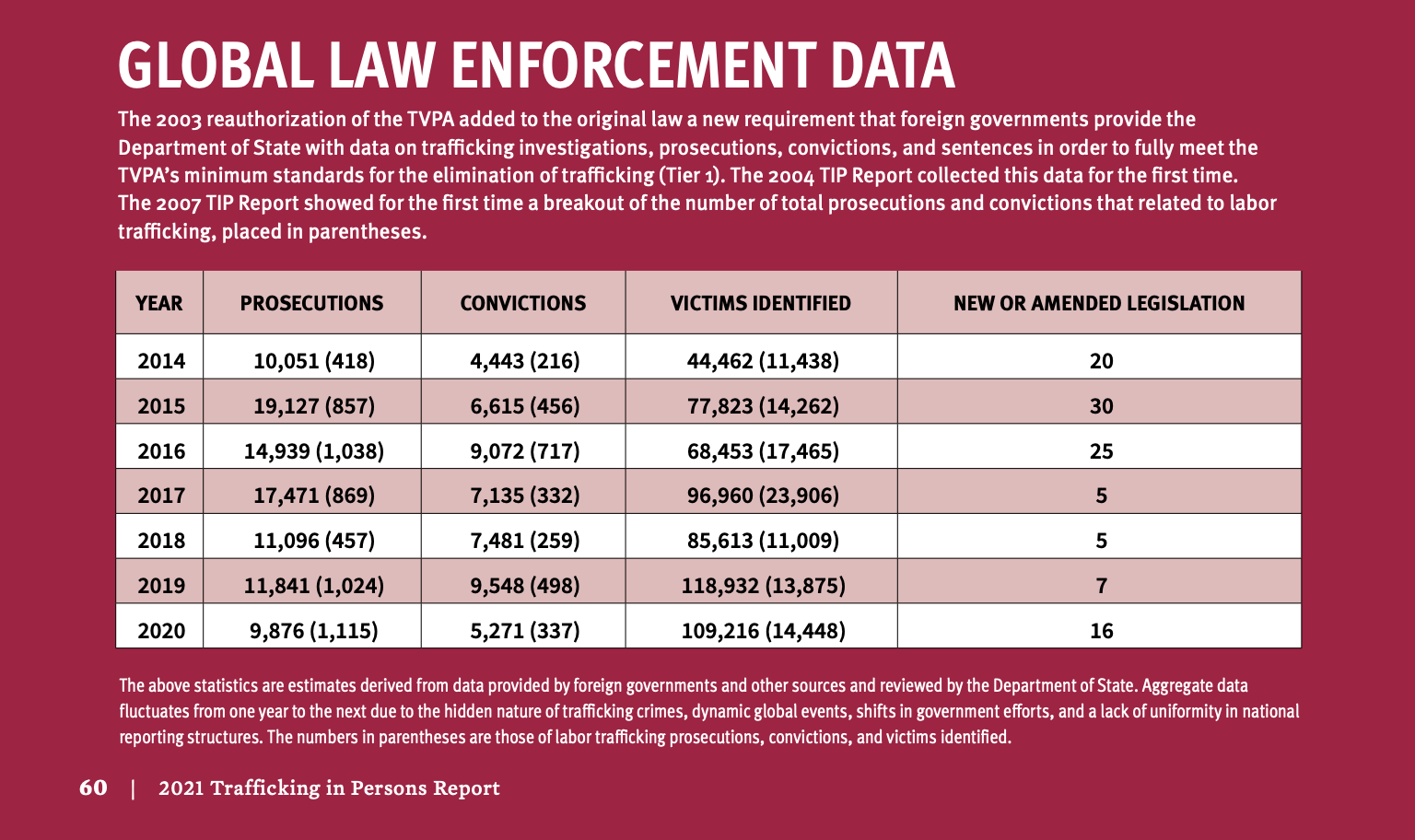

This year’s tier placements and global law enforcement data are as follows:

For a breakdown of each country narrative, tier ranking justification, and tier ranking by year, view the full TIP Report here.

The Federal Human Trafficking Report

The Human Trafficking Institute also published its annual Federal Human Trafficking Report—shining a light on the reality and scale of human trafficking in the United States, specifically.

The following estimates are based on prosecuted cases, and are not necessarily representative of all trafficking cases.

- 83% of active 2020 sex trafficking cases involved online solicitation, which is overwhelmingly the most common tactic traffickers use to solicit sex buyers.

- 59% of online victim recruitment in active sex trafficking cases occurred on Facebook.

- 65% of underage victims recruited online in 2020 active criminal sex trafficking cases were recruited through Facebook, while 14% were recruited through Instagram, and 8% were recruited through Snapchat.

- More than 1 in 3 (38%) prosecuted U.S. cases of sex trafficking in 2020 were self-reported by a victim, making it the most common way trafficking cases were reported to law enforcement. This percentage jumps to 67% when looking exclusively at adult victims.

- 59% of coercive tactics used by traffickers in prosecuted cases of trafficking were non-physical, compared to 41% of tactics involving physical coercion.

- Girls under the age of 18 are the most likely to be named as victims in trafficking prosecutions.

- 53% of the victims in trafficking prosecutions in the U.S. in 2020 were children (3% men, 3% boys, 44% women, 50% girls).

- 12% of child trafficking victims were 13 years old or younger.

- The most common pre-existing conditions that made sex trafficking victims vulnerable to trafficking include, in order of likelihood, substance dependency (43%, child victims 18%), having run away from home (30%, child victims 63%), being an undocumented immigrant (13%), being in foster care (10%, child victims 22%), experiencing homelessness (10%, child victims 9%), and having been trafficked in the past (9%, child victims 9%).

- With both sex trafficking and forced labor, it is rare that perpetrators kidnap strangers off the street.

- 24% of sex trafficking victims involved in active criminal cases were recruited by an intimate partner or spouse, 23% by a mutual friend, 14% by a friend or classmate, 14% by a drug dealer, 9% by a parent or guardian, 6% by a religious leader, 5% by an extended family member, and 3% by a landlord.

- The most common coercive means used against sex trafficking victims in active 2020 criminal cases were withholding pay (75%), physical abuse (59%), inducing or exploiting a substance dependency (48%), threatening physical abuse (44%), rape/sexual violence (31%), feigning romance (15%), and threatening a victim’s family (10%).

- Of the criminal sex trafficking charges filed in the U.S. in 2020, 35% qualified as sex trafficking due to the involvement of force, fraud, or coercion, 53% qualified as sex trafficking due to the involvement of a minor, and 12% involved both.

Related: How Porn Can Fuel Sex Trafficking

Where do we go from here?

Amidst all of the challenges of the past year, leaders in the fight against human trafficking rose to the occasion and remain dedicated to the fight—and you can, too. Learning the facts is a great first step.

Ghada Waly, Executive Director for UN Office on Drugs and Crime, says, “And yet in these difficult times, we see the best of humanity: frontline heroes, men and women risking their lives and going above and beyond to provide essential support for human trafficking victims.”

In the face of this current global crisis and what’s to come, we can join together as an international community to work together with the shared goal of preventing and combating human trafficking, protecting victims, and empowering survivors.

Click here to learn more about how pornography fuels sex trafficking.

Your Support Matters Now More Than Ever

Most kids today are exposed to porn by the age of 12. By the time they’re teenagers, 75% of boys and 70% of girls have already viewed itRobb, M.B., & Mann, S. (2023). Teens and pornography. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense.Copy —often before they’ve had a single healthy conversation about it.

Even more concerning: over half of boys and nearly 40% of girls believe porn is a realistic depiction of sexMartellozzo, E., Monaghan, A., Adler, J. R., Davidson, J., Leyva, R., & Horvath, M. A. H. (2016). “I wasn’t sure it was normal to watch it”: A quantitative and qualitative examination of the impact of online pornography on the values, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of children and young people. Middlesex University, NSPCC, & Office of the Children’s Commissioner.Copy . And among teens who have seen porn, more than 79% of teens use it to learn how to have sexRobb, M.B., & Mann, S. (2023). Teens and pornography. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense.Copy . That means millions of young people are getting sex ed from violent, degrading content, which becomes their baseline understanding of intimacy. Out of the most popular porn, 33%-88% of videos contain physical aggression and nonconsensual violence-related themesFritz, N., Malic, V., Paul, B., & Zhou, Y. (2020). A descriptive analysis of the types, targets, and relative frequency of aggression in mainstream pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(8), 3041-3053. doi:10.1007/s10508-020-01773-0Copy Bridges et al., 2010, “Aggression and Sexual Behavior in Best-Selling Pornography Videos: A Content Analysis,” Violence Against Women.Copy .

From increasing rates of loneliness, depression, and self-doubt, to distorted views of sex, reduced relationship satisfaction, and riskier sexual behavior among teens, porn is impacting individuals, relationships, and society worldwideFight the New Drug. (2024, May). Get the Facts (Series of web articles). Fight the New Drug.Copy .

This is why Fight the New Drug exists—but we can’t do it without you.

Your donation directly fuels the creation of new educational resources, including our awareness-raising videos, podcasts, research-driven articles, engaging school presentations, and digital tools that reach youth where they are: online and in school. It equips individuals, parents, educators, and youth with trustworthy resources to start the conversation.

Will you join us? We’re grateful for whatever you can give—but a recurring donation makes the biggest difference. Every dollar directly supports our vital work, and every individual we reach decreases sexual exploitation. Let’s fight for real love: